Sermon by Sister Sheila Flynn, OP

| The Practice of Gratitude | ||

Sunday at 11 am in the Church Sanctuary November 25, 2012 | ||

Come and consider the practice of gratitude for the manifold ways we are supported, challenged, and encouraged in our lives. Sister Sheila will tell us about the breaking open of lives at Kopanang, the group Sister Sheila founded twelve years ago, made up of the poorest of the poor, women living in the huge shack areas of Tskane and Langaville, South Africa. Sister Sheila will talk about two different economies that impact our world: the gift economy and the market economy. She will explain to us what the financial and moral support of this congregation has meant in the lives of the women of Kopanang. Joining Sister Sheila on the chancel will be Minister Emerita The Reverend Margot Campbell Gross, and from Kopanang, Silindile Twala. After the service, beautiful embroidered work of the women of Kopanang will be available for sale. Ministering in music will be Organist Reiko Oda Lane and Young Performers International Performing Chorus lead by Music Director Leela Pratt.

***

More on the replacement of Gift Economies with Market Economies. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gift_economy Gift economy

In anthropology and the social sciences, a gift economy (or gift culture) is a mode of exchange where valuable goods and services are regularly given without any explicit agreement for immediate or future rewards (i.e. no formal quid pro quo exists).[1] Ideally, voluntary and recurring gift exchange circulates and redistributes wealth throughout a community, and serves to build societal ties and obligations.[2] In contrast to a barter economy or a market economy, social norms and custom governs gift exchange, rather than an explicit exchange of goods or services formoney or some other commodity.[3]

Traditional societies dominated by gift exchange were small in scale and geographically remote from each other. As states formed to regulate trade and commerce within their boundaries, market exchange came to dominate. Nonetheless, the practice of gift exchange continues to play an important role in modern society.[4] One prominent example is scientific research, which can be described as a gift economy.[5]

The expansion of the Internet has witnessed a resurgence of the gift economy, especially in the technology sector. Engineers, scientists and software developers create open-source softwareprojects. The Linux kernel and the GNU operating system are prototypical examples for the gift economy's prominence in the technology sector and its active role in instating the use ofpermissive free software and copyleft licenses, which allow free reuse of software and knowledge. Other examples include: file-sharing, the commons, open access.

[edit]History

Contrary to popular conception, there is no evidence that societies relied primarily on barter before using money for trade.[6] Instead, non-monetary societies operated largely along the principles of gift economics, and in more complex economies, on debt.[7][8] When barter did in fact occur, it was usually between either complete strangers or would-be enemies.[9]

Lewis Hyde locates the origin of gift economies in the sharing of food, citing as an example the Trobriand Islander protocol of referring to a gift in the Kula exchange ring as "some food we could not eat," even though the gift is not food, but an ornament purposely made for passing as a gift.[10] The potlatch also originated as a 'big feed'.[11] Hyde argues that this led to a notion in many societies of the gift as something that must "perish".[citation needed]

The anthropologist Marshall Sahlins writes that Stone Age gift economies were, as evidenced by their nature as gift economies, economies of abundance, not scarcity, despite modern readers' typical assumption of abject poverty.[12]

Gift economies were replaced by market economies based on commodity money, as the emergence of city states made money a necessity.[13]

[edit]Characteristics

A gift economy normally requires the gift exchange to be more than simply a back-and-forth between two individuals. For example, a Kashmiri tale tells of two Brahmin women who tried to fulfill their obligations for alms-giving simply by giving alms back and forth to one another. On their deaths they were transformed into two poisoned wells from which no one could drink, reflecting the barrenness of this weak simulacrum of giving.[14] This notion of expanding the circle can also be seen in societies where hunters give animals to priests, who sacrifice a portion to a deity (who, in turn, is expected to provide an abundant hunt). The hunters do not directly sacrifice to the deity themselves.[14]

Many societies have strong prohibitions against turning gifts into trade or capital goods. Anthropologist Wendy James writes that among the Uduk people of northeast Africa there is a strong custom that any gift that crosses subclan boundaries must be consumed rather than invested.[15] For example, an animal given as a gift must be eaten, not bred. However, as in the example of the Trobriand armbands and necklaces, this "perishing" may not consist of consumption as such, but of the gift moving on. In other societies, it is a matter of giving some other gift, either directly in return or to another party. To keep the gift and not give another in exchange is reprehensible. "In folk tales," Hyde remarks, "the person who tries to hold onto a gift usually dies."[16]

Carol Stack's All Our Kin describes both the positive and negative sides of a network of obligation and gratitude effectively constituting a gift economy. Her narrative of The Flats, a poorChicago neighborhood, tells in passing the story of two sisters who each came into a small inheritance. One sister hoarded the inheritance and prospered materially for some time, but was alienated from the community. Her marriage ultimately broke up, and she integrated herself back into the community largely by giving gifts. The other sister fulfilled the community's expectations, but within six weeks had nothing material to show for the inheritance but a coat and a pair of shoes.[17]

[edit]Examples[edit]Pacific islanders

Pacific Island societies prior to the nineteenth century were dominated by gift exchange.[citation needed] Gift-exchange still endures in parts of the Pacific today; for example, in some outer islands of the Cook Islands.[18] In Tokelau, despite the gradual appearance of a market economy, a form of gift economy remains through the practice of inati, the strictly egalitarian sharing of all food resources in each atoll.[19] On Anuta as well, a gift economy called "Aropa" still exists.[20]

There are also a significant number of diasporic Pacific Islander communities in New Zealand, Australia, and the United States that still practice a form of gift economy. Although they have become participants in those countries' market economies, some seek to retain practices linked to an adapted form of gift economy, such as reciprocal gifts of money, or remittances back to their home community. The notion of reciprocal gifts is seen as essential to the fa'aSamoa ("Samoan way of life"), the anga fakatonga ("Tongan way of life"), and the culture of other diasporic Pacific communities.[21]

[edit]Papua New Guinea

The Kula ring still exists to this day, as do other exchange systems in the region, such as Moka exchange in the Mt. Hagen area, on Papua New Guinea.[citation needed]

[edit]Native Americans

Native Americans who lived in the Pacific Northwest (primarily the Kwakiutl), practiced the potlatch ritual, where leaders give away large amounts of goods to their followers, strengthening group relations. By sacrificing accumulated wealth, a leader gained a position of honor.[citation needed]

[edit]Mexico

In the Sierra Tarahumara of North Western Mexico, a custom exists called kórima. This custom says that it is one's duty to share his wealth with anyone.[22]

[edit]Spain

In place of a market, anarcho-communists, such as those who inhabited some Spanish villages in the 1930s, support a currency-less gift economy where goods and services are produced by workers and distributed in community stores where everyone (including the workers who produced them) is essentially entitled to consume whatever they want or need as payment for their production of goods and services.[23]

[edit]Information gift economies

Information is particularly suited to gift economies, as information is a nonrival good and can be gifted at practically no cost.[24][25] In fact, there is often an advantage to using the same software or data formats as others, so even from a selfish perspectve, it can be advantageous to give away ones information.

[edit]Science

Non-commercial scientific research is often considered to be a gift economy. Scientists who perform research and publish their findings in journals and talk about their work in conferences without remuneration. Though authors do not enjoy profits from publishing, subscribing to the journals themselves can be expensive and thus publishers limit access to these intended communal gifts of information. The open access movement makes research available online for far lower costs than traditional publishing. By avoiding prohibitively large subscription fees, this increases the circulation of knowledge and further draws it away from market exchange. Other scientists freely refer to other's research. Persons and institutions with access to these articles can therefore benefit from the increased pool of knowledge. The original scientists receive no direct benefit from making available their research, except an increase in their reputation. Failure to cite and give credit to original authors (thus depriving them of prestige due) is considered improper behavior.[26]

***

Potlatch

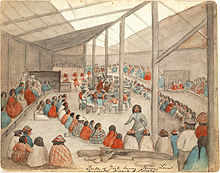

A potlatch[1][2] is a gift-giving festival and primary economic system[3] practiced by indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast of Canada and United States. This includes Heiltsuk Nation, Haida, Nuxalk, Tlingit, Makah, Tsimshian,[4] Nuu-chah-nulth,[5] Kwakwaka'wakw,[3] and Coast Salish[6] cultures. The word comes from the Chinook Jargon, meaning "to give away" or "a gift"; originally from the Nuu-chah-nulth word p̓ačiƛ, to make a ceremonial gift in a potlatch.[1] It went through a history of rigorous ban by both the Canadian and United States' federal governments, and has been the study of many anthropologists.

[edit]Overview

Different events take place during a potlatch, like singing and dancing, sometimes with masks or the real regalia, such as Chilkat blankets, the barter of wealth through gifts, such as dried foods, sugar, flour, or other material things, and sometimes money. For many potlatches, spiritual ceremonies take place for different occasions. This is either through material wealth such as foods and goods or non-material things such as songs and dances. For some cultures, such as Kwakwaka'wakw, elaborate and theatrical dances are performed reflecting the hosts' genealogy and cultural wealth. Many of these dances are also sacred ceremonies of secret societies like the hamatsa, or display of family origin from supernatural creatures such as the dzunukwa. Typically the potlatching is practiced more in the winter seasons as historically the warmer months were for procuring wealth for the family, clan, or village, then coming home and sharing that with neighbors and friends.

Within it, hierarchical relations within and between clans, villages, and nations, are observed and reinforced through the distribution or sometimes destruction of wealth, dance performances, and other ceremonies. The status of any given family is raised not by who has the most resources, but by who distributes the most resources. The hosts demonstrate their wealth and prominence through giving away goods. Chief O'wax̱a̱laga̱lis of the Kwagu'ł describes the potlatch in his famous speech to anthropologist Franz Boas,

Celebration of births, rites of passages, weddings, funerals, namings, and honoring of the deceased are some of the many forms the potlatch occurs under. Although protocol differs among the Indigenous nations, the potlatch will usually involve a feast, with music, dance, theatricality and spiritual ceremonies. The most sacred ceremonies are usually observed in the winter.

It is important to note the differences and uniqueness among the different cultural groups and nations along the coast. Each nation, tribe, and sometimes clan has its own way of practicing the potlatch with diverse presentation and meaning. The potlatch, as an overarching term, is quite general, since some cultures have many words in their language for various specific types of gatherings. Nonetheless, the main purpose has been and still is the redistribution of wealth procured by families.

[edit]History

Before the arrival of the Europeans, gifts included storable food (oolichan, or candlefish, oil or dried food), canoes, and slaves among the very wealthy, but otherwise not income-generating assets such as resource rights. The influx of manufactured trade goods such as blankets and sheet copper into the Pacific Northwest caused inflation in the potlatch in the late 18th and earlier 19th centuries. Some groups, such as the Kwakwaka'wakw, used the potlatch as an arena in which highly competitive contests of status took place. In some cases, goods were actually destroyed after being received, or instead of being given away. The catastrophic mortalities due to introduced diseases laid many inherited ranks vacant or open to remote or dubious claim—providing they could be validated—with a suitable potlatch.[7]

The potlatch was a cultural practice much studied by ethnographers. Sponsors of a potlatch give away many useful items such as food, blankets, worked ornamental mediums of exchange called "coppers," and many other various items. In return, they earned prestige. To give a potlatch enhanced one's reputation and validated social rank, the rank and requisite potlatch being proportional, both for the host and for the recipients by the gifts exchanged. Prestige increased with the lavishness of the potlatch, the value of the goods given away in it.

[edit]Potlatch ban

Main article: The Potlatch Ban (Canada)

Potlatching was made illegal in Canada in 1884 in an amendment to the Indian Act[8] and the United States in the late 19th century, largely at the urging of missionaries and government agents who considered it "a worse than useless custom" that was seen as wasteful, unproductive, and contrary to civilized values.[9]

The potlatch was seen as a key target in assimilation policies and agendas. Missionary William Duncan wrote in 1875 that the potlatch was "by far the most formidable of all obstacles in the way of Indians becoming Christians, or even civilized."[10] Thus in 1884, the Indian Act was revised to include clauses banning the Potlatch and making it illegal to practice. Section 3 of the Act read,

Eventually the potlatch law, as it became known, was amended to be more inclusive and address technicalities that had led to dismissals of prosecutions by the court. Legislation included guests who participated in the ceremony. The indigenous people were too large to police and the law too difficult to enforce. Duncan Campbell Scott convinced Parliament to change the offence from criminal to summary, which meant "the agents, as justice of the peace, could try a case, convict, and sentence."[12] Even so, except in a few small areas, the law was generally perceived as harsh and untenable. Even the Indian agents employed to enforce the legislation considered it unnecessary to prosecute, convinced instead that the potlatch would diminish as younger, educated, and more "advanced" Indians took over from the older Indians, who clung tenaciously to the custom.[13]

[edit]Continuation

Sustaining the customs and culture of their ancestors, indigenous people now openly hold potlatch to commit to the restoring of their ancestors' ways. Potlatch now occur frequently and increasingly more over the years as families reclaim their birthright. The ban was only repealed in 1951.[14]

|

No comments:

Post a Comment